Papers

Iranian Society 40 Years after the Revolution

—Women Removing their Headscarves and Globalization in Farming Villages—

Mari Nukii (Research Fellow, JIIA)

(Translated by Luke Schroeder, Master’s Candidate at Georgetown University and the JIIA Intern)

On December 27, 2017, almost 40 years after revolutionaries marched down Enqelab (Revolution) Street in Tehran, a woman stood waving her headscarf in the air like a flag, creating an uproar in the conservative country. Moved by the image, videos of her immediately went viral on social media, spread by supporters. This was just one act of protest that occurred throughout Iran by the end of that year.

With the foundation of an Islamic Republic as a result of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the new leadership aimed to inscribe Islamic law into politics, society, culture, and daily life. As a symbol of this change, women were required to wear the veil in public spaces.

During the liberal reform era of President Mohammad Khatami in the late 1990s, laws restricting female clothing and dating were relaxed. Tehran today looks almost completely different compared to then. Women confidently strut down the street in leggings and short blouses, with their scarves only covering the back of their heads and their hair blowing in the breeze. As a writer with the experience of being arrested by the morality police in 1997 for wearing a “slovenly white half coat,” it feels like a different age.

At a speech on February 11 last year for the 39th anniversary of the revolution, President Hassan Rouhani said, “It is difficult for young people that are feeling so pressured by Islamic law, so to properly hear their dissatisfaction, we should hold a national referendum.” But later in May that year, the Trump administration withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), weakening the moderate Rouhani and taking away any political capital he had with the conservatives for a referendum on the veil.

Since the end of the 19th century, Iranian nationalist movements have always begun in the cities. But in 2017, due to increasing economic hardship, disparate rural towns and farming villages became the main stage for countrywide protests and calls for an end to the Islamic system.

To counter the prevailing Western criticism that Iran is “reviving a reactionary Islamic system,” the Iranian leadership has strived towards modernization of rural areas and the spread of education. This push bore fruit, as even the most remote parts of Iran have running water, electricity, and gas, and people have been able to lead richer lives than foreigners imagine. In 1979, there were only about 4000 electrified villages, but by 2003 there were over 47,000, with 96.7% of Iran’s population able to access electricity. Households with indoor plumbing have also increased from 74.5% of the population in 1978 to 92.8% in 1994. Gas distribution now reaches over 70% of farming villages.

Education has also been a great success, as the literacy rate among those fifteen and older in 1976 was only at 36.5%, but by 2016 reached 85.5%. Looking only at younger Iranians, literacy climbed to over 98.1%. The rate of students attending tertiary education is around 70% (of which 60% are women according to UNESCO 2019), which is higher than even Japan (57.9%). More than half of Iranians use the internet. After the revolution, the government began to regulate the influx of Western culture as a “symbol of corruption,” so things like Hollywood movies and Western pop and rock music were banned. Regular citizens starved for information from abroad used various means to access websites and social media that were blocked by the government. Watching them do this, I could not help but feel that it has raised the computer literacy of Iran.

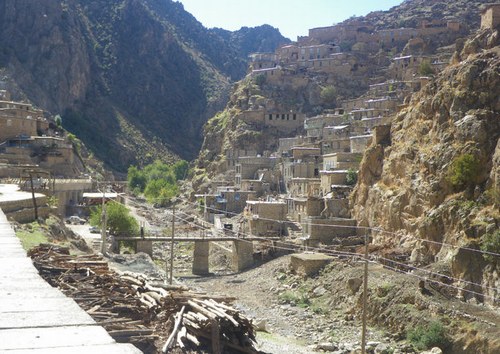

In November 2018, I visited the remote and beautiful Iranian-Kurdish village of Palangan in the northwestern part of the country. While there I took a commemorative photo with Kurdish women in their multicolored native dress. They requested of me, “Please send us the picture on WhatsApp!” But I responded, “I cannot,” leaving them very surprised and disappointed.

Iran has been under severe sanctions since 2006 due to its nuclear program, but it has developed its own cashless system and an Iranian Uber and Twitter. Unlike Japan’s My Number system, Iran has moved forward with a plan to let citizens use their national identification cards to pay for public utilities and complete state administrative applications. Even under sanctions, Iran has continued to grow its digital economy all on its own.

The digital revolution has allowed young Iranians in the countryside opportunities to access information from around the world. However, this has had the effect of further increasing dissatisfaction with living under the Islamic system, as well as making easier the possibility of exposure to external incitement.

In fact, Iranian dissident group Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MKO) has been spreading rumors about the close relationship between Trump administration officials, Israeli intelligence agencies, and Saudi Arabia’s royal family. In recent years, its aim has been to cause the internal collapse of the Islamic system through the dissemination of information meant to stir up social unrest. Certainly, about 70% of the population was born after the revolution, and most have had to the carry the burden of antagonistic foreign policies and economic sanctions. Many have misgivings about continuing to support the Islamic system.

On the other hand, this does not mean widespread support for the “traitorous” MKO among those suffering under American sanctions. Rather, in preparation for attacks from America and Israel, the primarily hardline conservative Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps has steadily gained in strength.

(Draft completed on May 13, 2019)

※This is an English translated version of the article originally published in Mita-Hyoron, Keio University, No. 1234 (June 2019).

Japanese version https://www.mita-hyoron.keio.ac.jp/featured-topic/2019/06-3.html

(2019-07-31)